NELF sees boost in energy behind its core principles

By: Kris Olson March 10, 2023

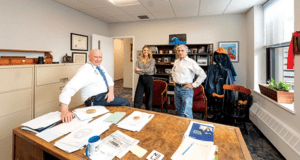

The New England Legal Foundation is having a moment.

For the first time in the organization’s 46-year history, it raised more than $1 million in donations in 2022, which President Daniel B. Winslow attributes to an increased “hunger for free enterprise.”

“There is a real renewed interest in the belief in the American dream,” Winslow says.

There were more startup businesses formed last year in the United States than in the next nine countries on the list combined, he notes.

Having Winslow — a former District Court judge who served as chief legal counsel to Gov. Mitt Romney — as the nonprofit public interest law firm’s “emissary” since October 2021 has not hurt fundraising efforts either, adds NELF senior staff attorney Ben G. Robbins.

NELF has also recently buffed up its balance sheet by playing the Boston commercial real estate market well. It sold its former headquarters at the height of the market and is now settling into new digs in Downtown Crossing. That has opened the door for the firm dedicated to free enterprise to raise its ambitions for the events it puts on.

Winslow hosts a podcast, “Sidebar with Judge Dan Winslow,” which has 14,000 followers and utilizes Fireside, the interactive streaming platform co-founded by former Google technology whiz Falon Fatemi and “Shark Tank” panelist and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban.

NELF is also now a certified provider of continuing legal education in all five New England states.

Then there are the legal victories. NELF lent its voice to the effort to end Boston’s eviction moratorium as the pandemic loosened its grip, and it took a lead role when officials seemed to be wavering on their commitment to return surplus state tax revenue to taxpayers as required under G.L.c. 62F.

NELF has also supported the winning side of several notable Supreme Judicial Court and 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decisions.

But if Winslow, his staff and board of directors have their way, this will be just the beginning. Among Winslow’s goals are changing the face of NELF, literally, by continuing to diversify its board and state councils.

The organization has also begun to raise the funds to launch what is tentatively titled the Equalizer Institute, a free legal clinic that would help entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups, including Black people, women, new Americans and veterans, get their businesses off the ground.

‘Partisan’ to rule of law

To board Chair Kevin P. Martin, a lawyer at Boston’s Goodwin, NELF fills a unique role in the local political and legal landscape.

Many assume that a group that advocates for free enterprise and private property rights is conservative, Martin says. But NELF is “studiously nonpartisan” and will turn down cases if they veer too far into pitched political battles, which Martin knows from personal experience.

Martin had been tapped in 2017 to argue the appeal to the SJC challenging the cap on charter school enrollment in Massachusetts and had sought NELF’s support in an amicus brief. But NELF took a pass, citing its disparate internal views on charter school expansion.

On the other hand, Martin was able to convince NELF to back his clients’ challenge to the millionaires’ tax ballot initiative a few years ago.

A key facet of that issue was that it involved a “structural question” of “how do we decide what gets into the state constitution?” he explains.

This is not uncommon of the appeals in which NELF attempts to exert its influence, its staff and board say. Considerations about the rule of law and good governance are often at the forefront, with benefits to any political constituency almost accidental, at least as far as NELF’s staff and board are concerned.

A case in point is what Robbins describes as the “prophylactic involvement” in what seemed to be a brewing battle over the tax rebates under Chapter 62F, which NELF helped to short circuit.

Chapter 62F became law as the result of a voter initiative petition back in 1987, and 35 years later — with taxpayers on the cusp of reaping its benefit — a bill was filed to undo it. To NELF, the taxpayers had a “vested property right,” Winslow says.

“We were there as advocates for rule of law,” he says.

In the end, not only did the state auditor wind up complying with her duties in advance of the statutory deadline, but Gov. Charlie Baker decided to turn the tax credit under the law into a direct refund, with checks arriving in mailboxes by the end of 2022.

“It was a better result than I think any of us had ever anticipated,” Robbins says.

Robbins sees NELF’s involvement in the legal effort to end Boston’s eviction moratorium — a case ultimately dismissed as moot — through much the same lens. It was as much about the lack of legislative authorization and a violation of the state’ s Home Rule Amendments as it was ensuring the financial survival of landlords and property owners, many of modest means, Robbins says.

Timothy J. Parilla brings to his service on NELF’s board the perspective of in-house counsel, previously for the daily fantasy sports company DraftKings and now the artificial-intelligence-powered contract management company LinkSquares.

He suggests that politics tends to take a back seat when pandemic restrictions and other government regulations are adversely affecting a business’s bottom line.

“At the end of the day, you forget about your politics when people are threatening your livelihood,” he says.

Answering critics

Sometimes NELF plays into a perception — perhaps unintentionally — that it is wading into partisan waters.

Earlier this year, NELF was spotted at what WGBH described as a “summit” for conservative advocacy groups seeking to position themselves “as a counterpoint to left-leaning environmental activists.”

Boston class action attorney and recent attorney general candidate Shannon Liss-Riordan also notes that NELF “always seems to pop up” whenever there is an important case involving employees’ rights, and always on the employers’ side. It has lent its support — gratuitously, in her view — to large corporations like Lyft and Grubhub.

“It’s a little curious to me why major corporations need the help of a nonprofit organization to make their point in court,” she says.

More typically, you would see amicus briefs filed in support of marginalized parties who have fewer resources, she adds.

But aside from the failed attempt to get onto the ballot an initiative that would have enshrined gig workers as independent contractors, NELF has a pretty good record of winding up on the winning side of appellate decisions, including on wage issues, notes staff attorney John Pagliaro.

Moreover, the SJC’s decisions in support of NELF’s favored position have often been unanimous, and the composition of the court is “not exactly seven Scalias,” he notes.

“If you can’t engage the argument, you have to attack the debater,” Winslow adds. “It just goes with the territory.”

Winslow says he has and will continue to work with people from across the political spectrum to advance what NELF considers to be “foundational values, not conservative or liberal values”: free enterprise, property rights, rule of law, and inclusive growth.

“There’s room in that mission for people of all political stripes,” Winslow insists.

The battles ahead

As for what is atop NELF’s agenda at the moment, Pagliaro on March 6 filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Supreme Court case Tyler v. Hennepin County, Minnesota. The issues in the case are whether the taking and selling of a home to satisfy a debt to the government, and keeping the surplus value as a windfall, violates the Fifth Amendment’s takings clause; and whether the forfeiture of property worth far more than needed to satisfy a debt is a fine within the meaning of the Eighth Amendment.

In Tyler, NELF’s brief supports the petitioner, a 94-year-old Minnesota woman who failed to pay $2,311 in taxes on her condo, which became $15,000 with penalties and interest. The county took title to the condo and sold it, retaining all $40,000 of the proceeds.

Massachusetts is one of at least 11 states in which such “equity theft” persists. NELF’s brief lays out the history of how English courts had come to recognize home equity as a form of property decades before the colonies won their independence and before the Constitution was written.

With a brief filed late last year, NELF is also hoping to convince the Supreme Court to take Loper Bright Enterprises, et al. v. U.S. Secretary of Commerce, et al., a case implicating the doctrine of Chevron deference.

In Loper Bright, the National Marine Fisheries Service — without any basis in the law’s text, according to Robbins, the brief’s author — has grafted onto the 1996 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act a requirement that owners of Atlantic herring vessels pay the salaries of the monitors they are required carry on board during their fishing trips.

Compliance would cost an estimated $710 a day and reduce the boat’s annual revenue by 20 percent.

In Robbins’ view, Loper Bright presents a classic example of Congress addressing a particular issue in one part of a statute but remaining silent in another section, which should be interpreted as a deliberate silence. That the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals somehow ruled otherwise is mystifying, he says.

Parilla believes that NELF can also help respond to the burgeoning awareness within Boston’s startup ecosystem and beyond about “macroeconomic issues in case law” and how those issues may impact the way that those businesses grow and operate.

Newer general counsel were not “brought up” with an appreciation for the importance of not just reviewing contracts but following developments in case law. NELF can help ensure that that segment of the legal community does not remain in the dark about such developments “until it’s too late.”

Then there is the Equalizer Institute, which Winslow acknowledges is a “different path for us.”

At this point, NELF is in the process of raising money to launch its first clinic, in which at least one law school has expressed an interest in staffing, Winslow says.

NELF has begun reaching out to corporations and philanthropic foundations, and the Equalizer Institute will also be the beneficiary of a “Beantown Beanfest” event in June.

“Once we get to a point of critical mass to be able to launch a proof of concept, we will do that,” Winslow says.

But Winslow is already envisioning the impact the institute will have on people’s lives, which he believes will “move donors and move hearts and minds to get more people behind it.”

Winslow points to “a massive gap in the law right now.” Civil legal aid, where it exists, is geared toward individual representation, not entrepreneurial ventures.

What NELF hopes to do is import the civil legal aid model — staff counsel augmented by law students and pro bono attorneys — to provide a year’s worth of free corporate legal services to anyone who would not be able to afford such services otherwise to “get them to the starting line and then let them go.”

“The Equalizer Institute concept has the potential to disrupt the legal ecosystem in the sense that the law students from some of our local law schools that might hang out a shingle when they graduate will have been trained by us on how to start up and launch a new business,” Winslow says. “We can then refer these new businesses to these newly minted lawyers to grow their practices.”

Black women launched a disproportionate share of the new businesses created during the pandemic, despite having the least access to capital, Winslow notes. NELF hopes to level the playing field. That would be a “win” for law students, firms, the profession and free enterprise, Winslow says.

“If we have that many wins, we’ll declare it a victory,” he says.